- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.world/post/26119689

I’ve heard English referred to as a Germanic-Romance creole, which makes a lot of sense when you consider how far removed it is from Old English.

[Sorry for the serious wall of text.]

I’ve heard those claims, too. They’re incorrect.

A creole is born from a pidgin (language fragments) glued into a coherent whole by grammatical rules made “on the spot”. Because of that, it’s practically impossible to analyse the grammar of a creole as the result of mutations over the grammar of any parent language.

However you can do it with English just fine:

- Phonetic erosion makes the case suffixes identical → case is now marked by word order → word order becomes syntactically fixed. Now you can’t say *“your famous blue raincoat at the shoulder torn was” without sounding like a weirdo.

- Phonetic erosion screws with the grammatical gender → grammatical gender gets ditched

- Phonetic erosion merges a bunch of verbal conjugations together → pronouns become obligatory + you need to spam aux verbs to convey subtler distinctions.

Even weirder features like do-support are easy to explain if you look at other Germanic languages (e.g. some German dialects spam tun “do” in a similar way.)

As a counterexample, look at Haitian - an actual creole, with the main parent languages being Fon and French. If you try to explain it as a grammatical descendant of either, you hit a wall already in the plurals:

- Fon: a-nòmàá “bird” vs. ǹ-nòmàá “birds” (source)

- French: l’oiseau /lwa.zo/ “the bird” vs. les oiseaux /le.zwa.zo/ “the birds”

- Haitian: zwazo “bird” vs. zwazo yo “birds”

Fon marks the plural mostly in the noun itself. French in theory does it, but most of the job is done by closely connected determiners, articles, and pronouns. If Haitian simply inherited the plural from either, you’d expect it to be marked before the noun, as a prefix of sorts. It doesn’t: the plural marker is a free word that goes after the noun phrase. And it is not bound to the noun, as zwazo mwen yo “my birds” shows.

I don’t think that contemporary English can be even remotely explained by creolisation. The Romance lexical influence is easier to explain if you had some sort of bilingual ruling chaste, exerting pressure over the language over a few centuries. One that would eat bœuf and porc while the plebs were raising cows and pigs. …and, well, that’s exactly what happened.

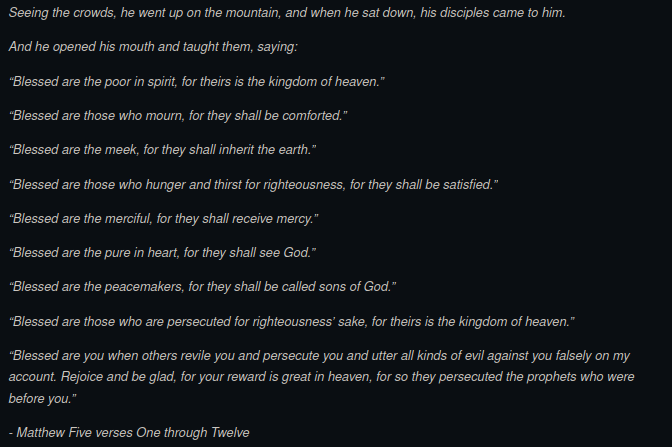

I did once make a conlang that was what an Old English-Old French creole would be like.

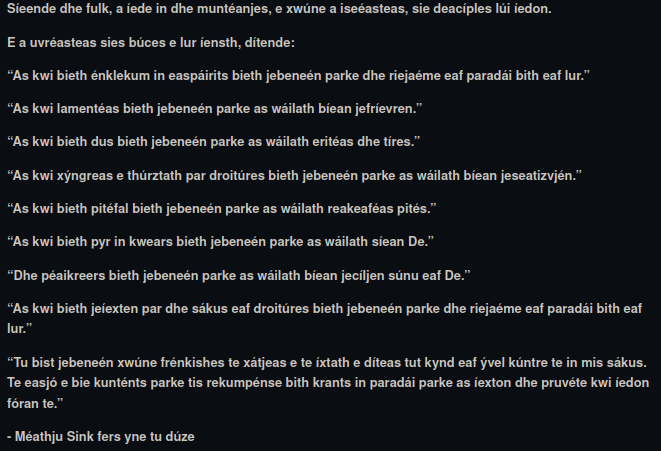

Here’s the Sermon on the mount:

Comments like yours give me the itch to work on my conlangs… I’ve been neglecting them for more than a year now.

And it’s really cool how you’re picking extinct OE features as building blocks for your conlang: ġe- → je- in participles, thou → tu (unless it’s a backed version of OF ⟨tu⟩ /ty/? IIRC /u/→/y/ was around 1100 or so), so goes on. It’s also interesting that you’re messing a bit with the prepositions, such as in dhe muntéanjes instead of on the mountains.

Just for curiosity, that ⟨dh⟩ represents /ð/, right? Was this some later, post-creolisation process?

<dh> does represent /ð/ in this romanization, yes.

As for <tu> being thou or tu, I’d have to check my design document.

- Langue Germanique romanisée

- Langue Romane germanisée

So similar it was guaranteed they’d fight wars so numerous they started being named just by duration.

Kind of like Greeks and Trojans, or Judeans and Samaritans.

Imagine being in the Thirty Years Wars and you realize it’s year 29 so the end is near

Imagine it’s year 9 of the Nine Years War and then they’re like “just joking, it’s the second Hundred Years War”.

No, they are very good at giving accurate names beforehand like the War to almost End War

Or the Scots and other Scots.

Damn Scots! They ruined Scotland!