Lukács’s work set off a firestorm among Western left theorists seeking to accommodate themselves to the new American imperium. In 1963, George Lichtheim, a self-styled socialist operating within the general tradition of Western Marxism while virulently opposed to Soviet Marxism, wrote an article for Encounter Magazine, then covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), in which he vehemently attacked The Destruction of Reason and other works by Lukács. Lichtheim accused Lukács of generating an “intellectual disaster” with his analysis of the historical shift from reason to unreason within European philosophy and literature, and the relation of this to the rise of fascism and the new imperialism under U.S. global hegemony.

This was not the first time, of course, that Lukács had been subjected to such strong condemnations by figures associated with Western Marxism. Theodor Adorno, one of the dominant theorists of the Frankfurt School, attacked Lukács in 1958 when the latter was still under house arrest for supporting the 1956 revolution in Hungary. Writing in Der Monat, a journal created by the occupying U.S. Army and funded by the CIA, Adorno charged Lukács with being “reductive” and “undialectical,” writing like a “Cultural Commissar,” and with being “paralysed from the outset by the consciousness of his own impotence.”

However, the 1963 attack on Lukács by Lichtheim in Encounter took on an added significance due to its absolute condemnation of Lukács’s The Destruction of Reason. In this work, Lukács had charted the relation of philosophical irrationalism—which first emerged on the European Continent, particularly in Germany, with the defeat of the 1848 revolutions, and that became a dominant force near the end of the century—to the rise of the imperialist stage of capitalism. For Lukács, irrationalism, including its ultimate coalescence with Nazism, was no fortuitous development, but rather a product of capitalism itself. Lichtheim responded by charging Lukács with having committed an “intellectual crime” in illegitimately drawing a connection between philosophical irrationalism (associated with such thinkers as Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson, Georges Sorel, Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, and Carl Schmitt) and the rise of Adolf Hitler.

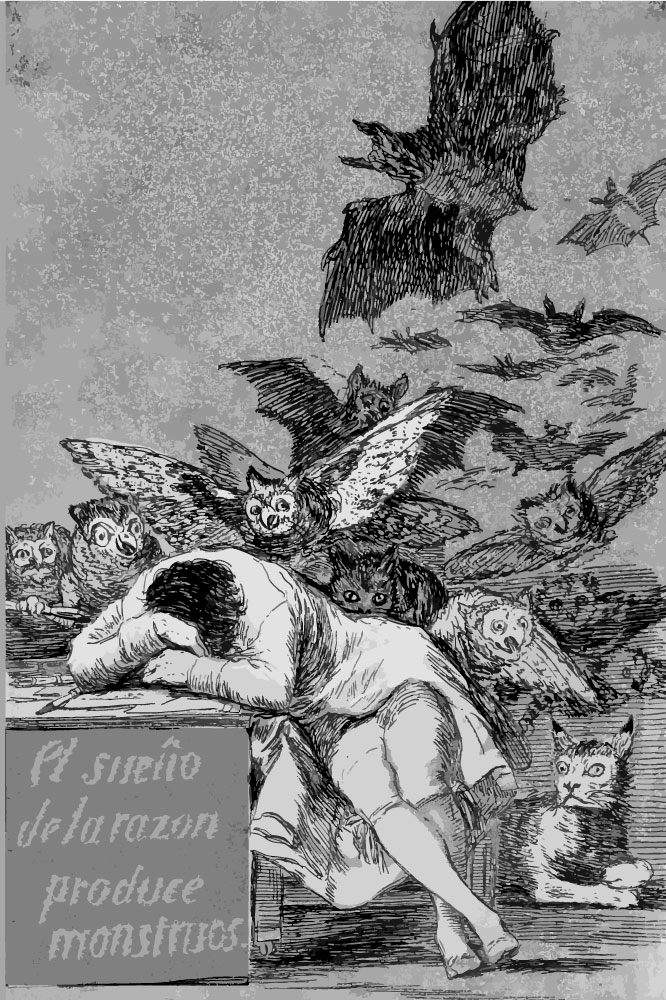

Lukács provocatively started his book by saying “the subject matter which presents itself to us is Germany’s path to Hitler in the sphere of philosophy.” But his critique was in fact much broader, seeing irrationalism as related to the imperialist stage of capitalism more generally. Hence, what most outraged Lukács’s critics in the West in the early 1960s was his suggestion that the problem of the destruction of reason had not vanished with the historic defeat of fascism, but that it was continuing to nurture reactionary tendencies, if more covertly, in the new Cold War era dominated by the U.S. imperium. “Franz Kafka’s nightmares,” Lichtheim charged, were treated by Lukács as evidence of “‘the diabolical character of the world of modern capitalism,'” now represented by the United States. Yet, Lukács’s argument in this respect was impossible to refute. Thus, he wrote, in terms still meaningful today:

In contrast to Germany, the U.S.A. had a constitution which was democratic from the start. And its ruling class managed, particularly during the imperialist era, to have the democratic forms so effectively preserved that by democratically legal means, it achieved a dictatorship of monopoly capitalism at least as firm as that which Hitler set up with tyrannic procedures. This smoothly functioning democracy, so-called, was created by the Presidential prerogative, the Supreme Court’s authority in constitutional questions, the finance monopoly over the Press, radio, etc., electioneering costs, which successfully prevented really democratic parties from springing up beside the two parties of monopoly capitalism, and lastly the use of terroristic devices (the lynching system). And this democracy could, in substance, realize everything sought by Hitler without needing to break with democracy formally. In addition, there was the incomparably broader and more solid economic basis of monopoly capitalism.

In these circumstances, irrationalism and the “piling up of cynical contempt for humanity,” Lukács insisted, was “the necessary ideological consequence of the structure and potential influence of American imperialism.” This shocking claim that there was a continuity in the relation of imperialism and irrationalism extending over the course of an entire century, from late nineteenth-century Europe, through fascism, and continuing in the new NATO imperium dominated by the United States, was strongly rejected at the time by many of those associated with the Western Marxist philosophical tradition. It was this, then, more than anything else, that led to the almost complete disavowal of Lukács’s later work (after his 1923 History and Class Consciousness) by left thinkers working in conjunction with the new post-Second World War liberalism.

Nevertheless, The Destruction of Reason was not subject to a systematic critique by those who opposed it, which would have meant confronting the crucial issues it raised. Instead, it was dismissed vituperatively out of hand by the Western left as constituting a “deliberate perversion of the truth,” a “700-page diatribe,” and a “Stalinist tract.” As one commentator has recently noted, “its reception could be summarized by a few death sentences” issued against it by leading Western Marxists.

A GLOWING ENDORSEMENT!!!

IF YOU READ THIS FAR YOU ARE OBLIGED!!!

Georg Lukacs - The Destruction of Reason-Penguin Random House LLC (Publisher Services) (2021).epub

0.9 MB https://files.catbox.moe/w2jp94.epub

Still, there was no denying the scale of the undertaking represented by The Destruction of Reason as a critique of the main traditions of Western irrationalism by the world’s then most esteemed Marxist philosopher. Rather than treating the various irrationalist systems of thought of the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries as if they had simply fallen from the sky, Lukács related them to the historical and material developments from which they emerged. Here, his argument relied ultimately on V. I. Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Irrationalism was, therefore, identified, as in Lenin, principally with historical-material conditions of the age of monopoly capitalism, the dividing up of the entire world between the great powers, and the geopolitical struggles over hegemony and spheres of influence. This was manifested in an economic-colonial rivalry between various capitalist states, coloring the entire historical context in which the new imperialist stage of capitalism emerged.

Today this fundamental material reality in many ways persists, but it has been so modified under the U.S. global imperium that a new phase of late imperialism can be said to have arisen, dating back to the end of the Second World War, merging immediately into the Cold War, and perpetuated, following a brief interregnum, in the New Cold War of today. Late imperialism in this sense corresponds chronologically with the end of the Second World War, the emergence of the nuclear age, and the beginning of the Anthropocene Epoch in geological history, which marked the advent of the planetary ecological crisis. The consolidation of global monopoly capital (more recently monopoly-finance capital), and the struggle by the United States—backed by the collective imperialism of the triad of the United States/Canada, Europe, and Japan—for global supremacy in a unipolar world all correspond to this phase of late imperialism.

For the Western left itself, the history of late imperialism has been primarily marked by the defeat of the revolts of 1968, followed by the demise of Soviet-type societies after 1989, which had as one of its primary consequences the collapse of Western social democracy. These events placed the Western left as a whole in a weakened position, ultimately defined by its general subordination to broad parameters of the imperialist project centered in the United States and its refusal to align with the anti-imperialist struggle, thus guaranteeing its revolutionary irrelevance.